Dr Stewart Mottram, Senior Lecturer in English, University Hull; Co-Investigator on the AHRC project, Risky Cities: Living with Water in an Uncertain Future Climate; and deputy director of the Leverhulme Doctoral Scholarships Centre for Water Cultures

The broad sweep of the Humber Estuary, the subject of our #HumberWalk21 series of blogs, is reimagined in Philip Larkin’s poem, ‘Here’ (1964), which describes ‘swerving to solitude’ east beyond Hull to the ‘Isolate villages’ and ‘neglected waters’ of Holderness. ‘The widening river’s slow presence’ shapes the lines and landscape of Larkin’s poem, and Larkin is only one of several writers who have found inspiration along the Humber’s shores.

Road junction on Sunk Island Road from geograph.org.uk

Our subject in this blog is Sunk Island, a parish of some 7500 acres bordered by the Humber Estuary to the south and surrounded to the north by a narrow channel, or drain, that separates the parish from the nearby villages of Ottringham and Patrington. The ‘North Channel Drain’, which runs beneath the bridge near Shrubbery Farm on the main Sunk Island Road from Ottringham, is all that remains of a channel that 400 years ago had been 1.5 miles wide.

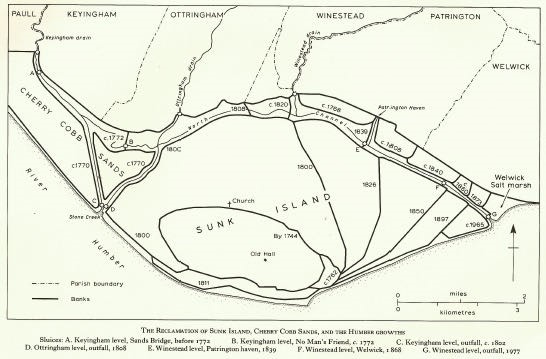

Sunk Island – like nearby Spurn Point – owes its existence to the Humber’s shifting sediments and currents, which over centuries has carried material washed from the Holderness cliffs into the Humber Estuary. Today’s Sunk Island first rose up from the Humber in the late sixteenth century and by the reign of Charles I (died 1649) it was a sand bank of about 7 acres. It was claimed as crown property and leased to Colonel Anthony Gilby (died 1682) on the understanding that Gilby would reclaim at least 100 acres of ‘drowned land’ within the first ten years of the lease. Over time, Gilby and his descendants progressively embanked and drained the land so that by 1850 some 5000 acres had been reclaimed from the sea for farming.

The Reclamation of Sunk Island. Reproduced from A History of the County of York East Riding, Vol. V (Oxford University Press, 1984), p. 136, by permission of the Victoria County History, University of London, and used in the Hubert Nicholson and Sunk Island: A Novel Place Reclaimed exhibition by Profs Jane Thomas and Briony McDonagh. The exhibition was shown on Sunk Island and at the Hull History Centre in 2017 and 2018 and supported by the AHRC Being Human Festival. Find out more here.

The Hull poet and politician, Andrew Marvell (1621-78), describes the arduous process of claiming ‘new-catched miles’ from the sea in his poem, ‘The Character of Holland’ (1653). The poem, written during the first Anglo-Dutch War (1652-54), seems on the surface to poke fun at the Dutch and their battles with the ‘barking waves’, but much of Marvell’s attack in the poem on Dutch efforts to reclaim land reflects back on the similar practices then underway in the Humber Estuary and elsewhere in eastern England during Marvell’s lifetime.

Marvell was born some three miles north of where Sunk Island village now stands, at the rectory in nearby Winestead in 1621. But in 1621, Winestead was much closer to the Estuary than it is today, and when Marvell was a boy, Sunk Island was only a sand bank visible at low tide. When Marvell returned to the area in 1674, to take part in a survey of the river Humber, he would have seen Gilby’s work to reclaim ‘the new-catched miles’ from the sea at Sunk Island for himself.

Andrew Marvell (1621-78), by Vincent Galloway (1894-1977). ©Hull Museums Collection, KINCM: 2005.3

But Marvell’s focus on the ‘barking waves [that] bait the forced ground’ also reminds us that land reclaimed from the sea is, then and now, acutely vulnerable to flooding. The medieval hamlets of Frismarsh and Tharlesthorpe lay somewhere in the region of the later Sunk Island, but were abandoned in the fourteenth century in the face of flooding from the Humber. The Hull journalist, poet, and novelist, Hubert Nicholson (1908-96) imaginatively recreates the moment this land was washed away in his 1956 novel, Sunk Island:

Men had forgotten in those parts what some few antiquaries in the cities could have told them – that before the rising there had been a swallowing. Before a sandbank arose in Charles the First’s reign, and grew to a mud-patch, and was grappled with bridges, and dyked and banked till all division disappeared; long before, six hundred years ago, the men who lived on the brim of the Riding saw a great island sink, with living towns aboard it, like some earthen Titanic. A slow catastrophe that left nothing behind it but the enigmatic name.

Hubert Nicholson, Sunk Island, 1956

Nicholson also writes in Sunk Island of the devastating floods of 1953 which saw much of Sunk Island submerged.

The former poet laureate, Ted Hughes (1930-98), might almost have rubbed shoulders with Hubert Nicholson when, between 1948-50, he spent his National Service at the RAF base at Sunk Island. Hughes, originally from Mytholmroyd, West Yorkshire, lodged at 4 Northside in the village of Patrington, and daily walked the two miles out to the brick radar station at Sunk Island, which can still be seen today to the right off Patrington Road as it runs south from Patrington Haven. Like Nicholson, Hughes found inspiration in the reclaimed landscape of Sunk Island, but also some trepidation at what he describes (in ‘Mayday on Holderness’, published in 1960) as ‘the unkillable North Sea [which] swallows all’.

The Humber Estuary off Sunk Island, ©Jonathan Thacker (licensed for re-use under CC BY-SA 2.0 Creative Commons License)

Humber communities, including those on Sunk Island, are still vulnerable to flooding, and our work on the Risky Cities project at the University of Hull gathers histories and stories of flooding from Hull and the Humber to help build climate awareness and help communities become more flood resilient, today and for the future. You can watch a short film about the project below and sign up for our mailing list here.

Want to know more?

You can read about the Hubert Nicholson and Sunk Island project at the University of Hull here.

Find out more about our work on the Rising Tide of Humber project to recreate seventeenth-century flood events in Andrew Marvell’s Hull here.

Or you can learn more about our Risky Cities project on our website and follow the project on twitter @Risky_Cities