Professor Briony McDonagh, project lead for Risky Cities, reflects on the project’s impacts in this blog, drawing on evaluation activity by the full team

The Risky Cities project uses a ‘learning histories’ approach to drive climate awareness, action and resilience. For us, learning histories are the foundation of place-based, historically-informed, creative community engagement. In our project, we’ve used histories and stories of living with water and flood over hundreds of years in one flood-prone city, Kingston-Upon-Hull (UK) to help make big global narratives about climate change tangible and relatable at the local level – and so drive anticipatory climate action.

Recent research shows that site-specific climate arts and locally-rooted stories of living with water and flood can help make global climate issues meaningful to audiences. Much of this work, including by geographers, has focused on climate communication – including the role of storytelling. Far less has been said about arts for anticipatory climate action. There are also very few large-scale studies evaluating the effectiveness of these approaches in driving behavioural change and building climate resilience. As a result, while art about climate crisis is now very common, arts and heritage approaches are not at present well integrated into policy toolkits for Action for Climate Empowerment (ACE).

At the same time, the potential of place-based, historically-informed approaches to facilitate action for climate empowerment has not been fully investigated. A handful of existing studies use recent flood memories, but none have made use of pre-twentieth century histories of living with water and flood in order to drive climate resilient actions today. And this despite the fact that city planners and global policy makers advocating for nature-based and ‘slow water’ solutions are drawing on past water management practices as models for contemporary schemes.

It is these research and policy gaps that Risky Cities addresses.

What are learning histories?

The term ‘learning histories’ was first developed at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the mid-1990s as a way of reflecting on the past in order to drive organisation learning and transformation. We borrowed and developed this term. For us, learning histories are multiple, jointly told stories, necessarily collaborative and creative. They fold together past, present and future in productive ways, so as to learn from the past to rethink the present and change the future.

This folding together happens in two main ways. Firstly, in the sense that place-based histories and stories are mobilised in the creative engagement activities, where they act as a hook for conversations about living with water and future climate change, as well as provide potential models for rethinking our future relationships with water and flood. They also help make big narratives about global climate change locally meaningful and relevant – and thus, drive behavioural change, anticipatory action and community-led climate solutions.

And secondly, in the sense that the conversations that took place in and around the engagement activities were themselves generative of further watery stories and experiences. These then contribute to the corpus of knowledge, understanding and experience within the team, our participants and wider community about histories and futures of living with and alongside water and flood. In this sense, our learning histories approach can be usefully understood as a participatory research method and novel addition to the toolkit for building climate action, empowerment and resilience.

Hull’s watery histories

Hull has long been a watery place. The town was not unique in being located in the green-blue zone between land and sea, but excellent historical sources mean we know more about when Hull flooded, how flood risk was managed, and who governed and managed water than for other English and Scottish towns.

The project drew on a range of sources including: extensive archival records; antiquarian histories; maps; newspapers; photographs; literary analysis of flood fictions in poetry, plays and folklore; and watery stories and flood experiences shared by community participants. Collectively, these allowed the team to reconstruct a flood timeline for Hull – revealing a history of repeated flood events affecting the town and surrounding areas in the seven centuries after its foundation in c. 1260 – and corpus of stories and experiences exploring people’s relationships with their watery environment.

The stories that emerge from the archive are primarily ones of surviving and thriving, of adaption and mitigation, of ongoing maintenance of water infrastructure and careful water governance, of living more or less successfully with water over many generations, rather than of flood-related disruption, disaster and cataclysm. To put it another way, living with water and flood was an integral part of working and dwelling in the medieval, early modern and modern town – a collective experience that was generative of what we have called elsewhere a ‘living with water mentality’.[1]

It is these histories, stories and experiences that we and our creative partners and commissioned artists drew on in our creative and participatory practice.

Does a learning histories approach work?

Short answer, yes!

We could give lots of examples of how we’ve successfully used learning histories in creative and/or arts-led engagement for climate action – from site-responsive theatrical performances at global climate summits to small-scale community engagement projects using textiles, creative writing and visual arts. Each of these has involved different relationships with creative partners and community participants. Each also offered different opportunities for assessing the effectiveness of our interventions amongst participants and audiences.

But to focus here on one project and its outcomes.

In the FloodLights project, we used large-scale public art as a tool for driving climate awareness and action. FloodLights consisted of three site-responsive, multimedia light and sound installations shown over four nights in October 2021 in Hull city centre, and attended by an audience of c. 11,000. We worked with project partners Absolutely Cultured, Yorkshire Water and the Living with Water Partnership, and some fantastic artists and creatives – poet Vicky Foster, multimedia creative studio Hidden Orchestra, Studio McGuire, and Barret Hodgson of Vent Media.

Together, we explored and illuminated Hull’s experiences of living with water, past, present, and future, utilising local histories, stories and landmarks to drive climate awareness and action. Development work on the project started in winter 2019/2020 with creative workshops involving students, young people, and community members. We used maps, folklore and stories from the archives as a prompt to discuss experiences of living with water in the city from the medieval period to today.

In this sense, the workshops formed part of a wider ser of co-creative practices used in the project which focused on generating two-way dialogue and knowledge exchange between academics, artists and community participants. For example, in one workshop artist Sarah Pennington also showed us how to make memory boxes from historical maps – a hands on activity which kept our bodies and minds busy while offering an opportunity to discuss potentially difficult experiences of the 2007 Hull floods. At the end of the workshop, participants (metaphorically) deposited their watery memories and experiences of the city – good or troubling – into the boxes.

Much delayed by Covid, the three large-scale public artworks were eventually shown in the city in autumn 2021. Our audience survey was completed by 470 of our 11,000 audience members, providing one of the largest datasets on audience responses to climate art in the published literature.

Our analysis of our survey results showed that FloodLights facilitated audiences to engage in climate and water action. For example, 64% of respondents reported that attending FloodLights made them think about climate futures, flood risk and living with water – and a third reported the behavioural changes they planned to make in relation to this.

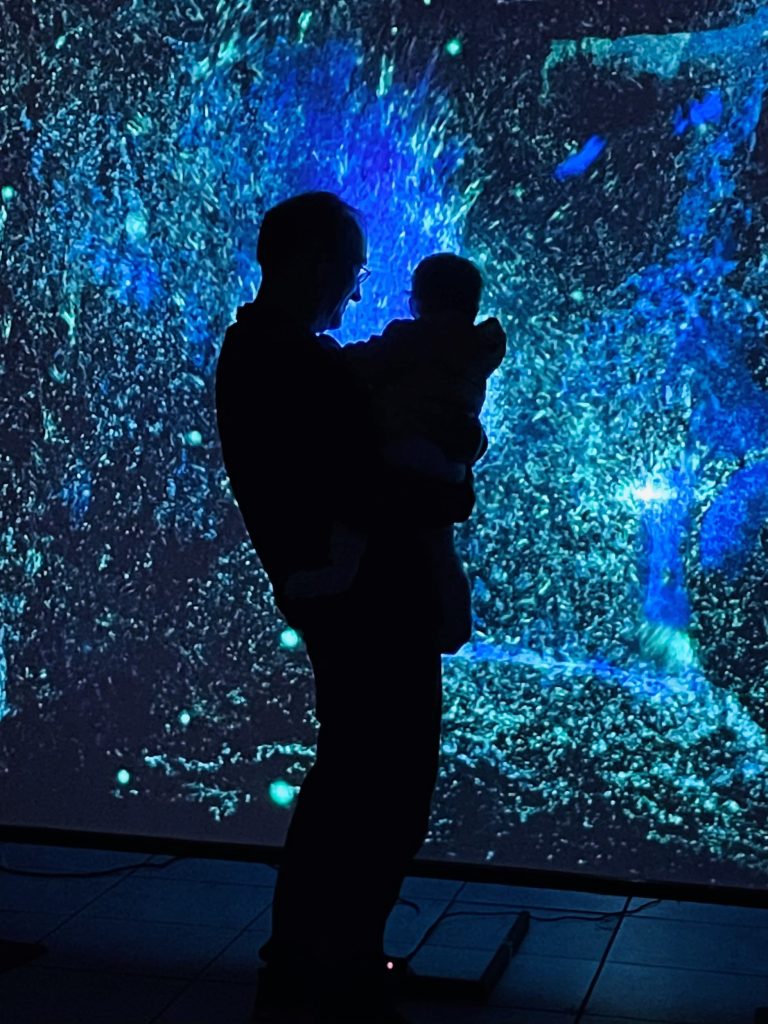

Each of the three installations responded to place and local histories in different ways. Overflow engaged specifically with the historical maritime legacy of the city’s built environment. Sinuous City led participants to immersive and personal experiences of flooding, and Sirens visualised imaginative aquatic entanglements between water and environment. Our survey demonstrates that each of these place-based approaches – especially the site-responsive installations which mobilised Hull’s watery histories and identities – were crucial in generating engagement and action towards climate resilience.

As a form of place-based historically-informed arts-led engagement FloodLights provided opportunities to make global narratives tangible at the local scale – and hence prompt climate action and behavioural change.

You can read our free preprint Place-based arts engagement and learning histories: an effective tool for climate action?

You can also learn more about the learning histories approach by reading our free preprint, Learning histories, participatory methods and creative engagement for climate resilience.

[1] B. McDonagh, H. Worthen, S. Mottram and S. Buxton-Hill, Living with water in medieval and early modern Hull, Environment and History (in review). Our thanks too to Flavia Manieri for sharing material from her forthcoming thesis on experiences of flooding in twentieth-century Hull.