Dr Kate Smith, Researcher, Flood Innovation Centre, University of Hull

Whether seen at eye-level from the train through Brough, or close at hand along the Trans-Pennine trail, the Humber between Brough and North Ferriby is a pretty tranquil place of shimmering mudflats, grazing sheep and quietly rippling tides. The occasional freight vessel gives little indication that the deep waters of the estuary are still one of the busiest shipping areas in the UK.

Image by David Wright, Humber Foreshore and Trans Pennine Trail - geograph.org.uk - 751586.jpg https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/deed.en

Whether seen at eye-level from the train through Brough, or close at hand along the Trans-Pennine trail, the Humber between Brough and North Ferriby is a pretty tranquil place of shimmering mudflats, grazing sheep and quietly rippling tides. The occasional freight vessel gives little indication that the deep waters of the estuary are still one of the busiest shipping areas in the UK.

We’re used to the idea of freight being unstacked from neat piles of shipping containers. But before there were lorries and trains, goods made their way to factories by boat. Often these were narrow-boats pulled by horses along the network of canals that were constructed from the mid-18th century. But for centuries the factories of the industrial North were served by wind-powered freight: up and down the Humber, cargoes were carried by sail-powered keels.

Keel Image courtesy of East Riding Museums

Keels are sturdy enough to cope with the strong currents in the Humber estuary, and shallow enough to make their way to inland ports. The relative simplicity of their rigging means that they can be safely sailed by two hands. Being wind-powered, they were cheap to operate.

Unlike narrowboat communities, keelmen and women didn’t live onboard. On both sides of the estuary there were well-established communities of keelmen and women, with a distinct work-related culture. Some of the material aspects of this culture have been preserved by charities like the Humber Keel and Sloop Preservation Society, and could once be seen at the (now closed) Waterways Museum in Goole.

Less well known is their textile culture. All along the Humber, as around the coast, mariners wore hand-knitted navy ganseys. These were so ubiquitous as to be a uniform for those working on the keels:

‘Our navy blue jerseys were home-knitted with a diamond pattern on the front and had high necks which fastened with two buttons on the left shoulder. Fastening had to be on the left as we carried things on the right shoulder. The guernseys had to be close-fitting and tight because loose clothing could so easily have caught on projecting parts of keel or lock…’

(Fletcher. 1975)

As with the fishermen’s gansey, the patterns observed in inland mariner’s jumpers have been written down and fixed to places and families. Local historian Penelope Lister Hemingway has documented the range and variety of Humber ganseys, noting that ‘compared to coastal ganseys, we have a paucity of evidence for the inland ones’ (2015, 78). What evidence there is indicates that the culture of gansey knitting was shared between inland and sea-going sailors, and points to cultural connections across the North Sea to Ghent, Le Havre and other European ports.

Despite their former ubiquity, relatively few examples of historic garments exist – it’s likely that older garments were cut up for rag rugs, or unwound for darning. Several examples of Humber ganseys were displayed at the Goole Waterways museum, each stitch still crisp and defined despite the garments’ age and wear. These examples suggest that there was some preference for bold, central panel designs often featuring a large diamond or star. The Humber Star pattern notated by Michael Pearson has been widely circulated among the gansey-making community.

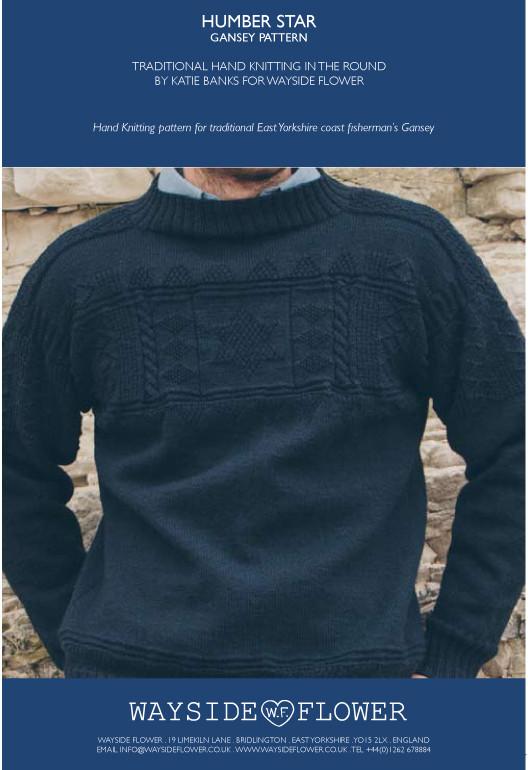

Humber Star pattern from Wayside Flowers

For their devotees, ganseys offer the modern wearer the same benefits as they did for historical keelmen: they are warm, cosy, breathable, stretchy and seamless. For the hand-knitter they offer both the physical and technical challenge of tiny stitches and heavy yarn knitted in the round on thin steel needles. For many enthusiasts, the detailed motifs are a real attraction.

Ganseys bring their fans a slower pace of experiencing the world. Much as the world of sail-powered boats reflects a gentler, slower (and very energy efficient) way of transporting goods, the process of creating a hand-knitted gansey offers a gentler, slower way of making. The workwear of industrial water transportation was made by hand, stitch-by- stitch, using locally-distinctive motifs and to fit each person.

Ganseys – like sail-powered freight – remind us that the industrial world was not just full of engines and dirt but was also powered by hand, by wind and by water. And just as the renewables industry has revived the Humber economy, so the rediscovery of regional hand-knitting styles has revived the tradition of gansey making in the Humber and beyond.

So, as you walk between Brough and North Ferriby, you may reflect on how changing economic and environmental tides shape our appreciation of the material culture around us. You may remember that these quiet waters were once dotted with sails, alive with navy-ganseyed keelmen and their families, and that we remain connected by these waters to cultures near and far.

References and links

Fletcher, Harry, A life on the Humber: keeling to shipbuilding, Faber and Faber, 1975

Pearson, Michael, Traditional knitting: aran, Fair Isle and fisher ganseys, Dover Publications, (1984) 2015

Lister Hemingway, Penelope, River Ganseys, Cooperative Press Ohio, 2015

https://keelsandsloops.org.uk/ Slabline newsletters

Humber Keel and Sloop Preservation Society